Curated by Mario D’Souza with HH Art Spaces.

Text with inputs by Madhurjya Dey

Exhibition Inputs: Divyesh Undaviya, Madhurjya Dey, Shruthi Pawels and Shaira Sequiera Shetty.

Ferality generates in the aftermath of human intervention - a setting free of the once captive into the wild.

Non-human (and more-than-human) entities have survived since the birth of the planet. They have over time, formed ecological worlds where they multiplied, formed codes and conducts of living together, and even evolved or mutated to survive. With the development of humans, came war and technologies and thus extraction - from the wheel to the reactor. These endeavours and their waste has spilled into these sacred, ancient worlds, contaminating and in some cases annihilating them. To move from interdependence to dominance is man’s biggest pride and folly.

The targeted erasure of ancestral, indigenous and natural histories tied to landscapes by these extractive mechanisms have accelerated extinctions and the climate crisis. In a world where - colonial, settler-colonial, industrial and xenophobic structures continue to afflict people, natural animal ecologies, how can rewilding teach us resilience? How can we learn from those that persevered and survived? How can flora, fauna and landscapes teach us ecologies interdependence and climates of care?

Through an invitation to over 45 artists, Feral Ecologies as a framework is an extended approach to ferality and ecology in its examination of forests and fables, bone and bird, landscapes and infrastructure, cultivation and contamination, time and churning. It examines the friction and alliances between the domesticated and wild.

Raja Boro | Dharmendra Prasad | Jayeeta Chatterjee | Biraaj Dodiya | Chetan Solanki

Staged between stars and volcanic ash, the cycle of natural, geological and cosmic materials present a possibility of cyclical death and renewal. Within these imaginations of cartography, astronomy, faith and residue emerge as conceptual frameworks for stories, legends, artefact and incidents. Raja Boro belonging to the Tibeto-Burman people settled in Assam, looks at the moon as a medium or a device that reflects the light of the sun onto the planet. This in-between references a state of suspension, where identity is based on either origins or ends - where one begins or it ends voluntarily, circumstantially or with force - a dependent identity that strives for determination. In a similar landscape, in the stillness of a moonless night, a luminous sun-like spirit grazes the tips of paddy-grass in Dharmendra Prasad’s Daaini. Rumoured to abduct children and turn them into animals, these witches survive in the silences of forests and fields. The economies fear often deprive us of the fertile possibilities of legends - where we may imagine spirits as keepers, as transformational instead of those that devour. In another landscape, the ancient survives as a craton in Hampi - a piece of the earth’s heart literally. Jayeeta Chatterjee’s Scars of Exploitation examines this heart in the aftermath of extraction and mining, where the hollows swell like waves, a deceptively beautiful scene of crime.

Biraaj Dodiya takes the dust of another core, in the aftermath of the volcanic eruption of Popocatépetl to lace paper with ash. This gesture at once commemorates geological time emerging from a violent seismic rupture to ‘mark’ planetary history. This event across millennia has provided a starting over for civilizations. She notes, “bearing traces of making and unmaking; the fragmentary nature of the material and its emotive physicality creates a faceted visual surface flickering between depth and imagined shadow, treading over the idea of land, air, and home”. The volcanic ash also preserved civilizations in the aftermath of eruptions (like in Pompeii) or produced new ecosystems. Chetan Solanki takes the language of an excavated fragment, where an ancient mural survives time.

Bhasha Chakrabarti | Ali Akbar PN | Madhukar Mucharla | Ashish Phaldessai | Madhurjya Dey

Bhasha Chakrabarty’s Study of Tippoo Sultan's Incredible White-Man-Eating Tiger Toy Machine is an oil on aluminum painting of the 18th century automaton known as “Tipu’s Tiger” in the collection of the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. The wooden “toy”, (also an 18-note organ) depicts a life size tiger mauling a British soldier. The mechanisms inside the tiger make it growl while one hand of the man moves and emits a wailing sound from his mouth. The tiger is a part of a group of caricatures commissioned by Tipu Sultan, the 18th century ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore, showing Europeans being attacked, tortured, and humiliated by tigers, elephants, or snakes in an apparent reclamation of the Western stereotype of Indian “natives” as savage beasts. The tiger, along with a majority of Tipu Sultan’s wealth and personal effects, was looted by the British duri the storming of Mysore in 1799. Next to Chakrabarty is Ali Akbar PN’s Reincarnation of Myth referencing "chonakakkuthira" - the horses traded to the Indian subcontinent, particularly as war animals for the militaries of various kingdoms specifically from the Malabar region, which witness the simultaneous development of the Gujarat sultanate and Sufi traditions. The image develop from the traditional depictions of local fakirs-saints mounted on horseback, weaves a complex dialogue between historical events and modern reinterpretations. These visual and cultural motifs create a compelling intersection, particularly in the context of contemporary narratives and attempts to reshape collective memory.

Belonging to the Madiga community, who are traditionally leather workers or tanners, Madhukar Mucharla uses rawhide to mount a critique of the varna that depict lower castes as pigs. Drawn onto rawhide, Mucharla’s pig with a broom tied to its tail. “The rawhide medium underscores the enduring nature of these narratives, suggesting that just as rawhide withstands time, so too do the stories and struggles of marginalized communities”.

Against the backdrop of flickering city lights filtering through a clouded sky (a bird’s view), Madhurjya places two fabricated sarkari logos of existing festivals - the Jatinga festival and Falcon festival - “that appear both administrative and dated. The music festivals, centered around bird watching and awareness, perpetuate the local myth of suicidal migratory birds”. These events celebrate migration and music at the cost of the re-routing and terrorizing the distant migratory birds such as amur falcons, black drones, green pigeons, hill partridge, emerald dove, tiger bitterns and necklaced laughing thrush, etc. Despite the evidence, the administration maintains the narrative to boost the district's ailing economy through tourism. Both the Department of Tourism and Forest are involved - collectively benefitting from a natural phenomenon promoted something supernatural.

Dola Shikder | Sumit Naik | Snigdha Tiwari | Jahnvi Soni | Khushbu Patel

A now extinct Thylacine lurks in a flowering grove in a garden in Dola Shikder’s work. It doesn’t exist, but it is present like it were an apparition, a memory of a not so distant past. One way to come to terms with irrevocable loss is to believe something never existed or was just a figment the mind - another is to seek, actively acknowledge its presence and remind us of our follies. Sumit Naik thinks of extinction by placing one of the most invasive species - the bullfrog - in a terrain of despair. This imagination of ‘invasive’, is also produced by extractive systems to cull animal’s claim to land. Snigdha Tiwari thinks of animals in the city - dogs, cats, cows amongst others. As our cities urbanize and the landscape changes everyday, how can our animals find their way home. This act of making the city unfamiliar and strange and its ‘in development’ state also leaves us disoriented about what our true home is. In Jahnvi Soni’s Unidentifiable II we see specimen-like objects in a translucent vitrine box. Seemingly familiar, these objects evade origin or classification Khushbu Patel thinks about the Venus flytrap, native to the wetlands of the Carolinas, this astounded early botanists with its almost animal-like predatory behavior. Its delicate body - lures, captures, and consumes insects - blurring the boundaries between plant and predator.

Nitheen Ramalingam | Urna Sinha | Digvijay Jadega | Kapil Jangid | Revathy Bapu | Gaurang Naik

Emerging from Ramalingam’s research in the history of agrarian class struggles in the Thanjavur delta region, he visited a few familiar villages with an experienced community organizer from the place. Here he was introduced to many local memorials including one erected for Manali Kandasamy. Now abandoned because he defected to the ruling party towards the end of his life, “I am meditating on the dual aspects of the departed leader: Revolutionary and a defector, but also on the larger decline of the working-class movement in the region”. Urna Sinha is also looking at graves as memorials, monuments perhaps. Unnamed and slowly being taken over by the wilderness, no names or signs are visible under layers of dust. They stand timeless. A saint or for a beloved, the grave remains both a commemoration of death and a resistance to being forgotten. Digvijay Jadeja remembers a site where two rivers meet - a memory of a friend who now only exists in photographs. “The hazy, dreamlike landscape and muted tones reflect the interplay of memory and imagination” and how they are also tied to site and nature. In Hometown, Kapil Jangid studies his ancestral village in northeastern Rajasthan, where a once-thriving lake is now dry farmland. “The lake, sustained by the Aravalli mountains, was a vital water source for the village community. Today, its dried bed is used for farming, but the absence of water has disrupted lives”. The dry lake is causing an internal migration, with the communities dependent on it being forced to look for labour jobs in cities. Revathy Bapu laments the loss of an old Gulmohar tree in Margao near the PWD building, “that covered the entire road, providing shelter from the sun and rain alike to passersby. We could tell the tree was unmistakably inhabited by an abundance of fauna as well, the reminder of whom was given every time we so much as drove past it, in the form of the sheer volume of their birdsong”. This work is a response to the utter shock of the tree being felled. Central to Gaurang Naik’s untitled work is also a tree stump - “mirroring a mining pit, evokes the scars left on the land. Encircling it, fallen Australian Acacia leaves symbolize the invasive spread of this non-native species, Introduced in the 1980s to cover mining dumps, over decades these fast-growing trees have spread uncontrollably into forests, displacing native flora and masking the true extent of ecological devastation”.

Sahil Naik | Rai | Divyesh Undaviya | Sheshdev Sagaria

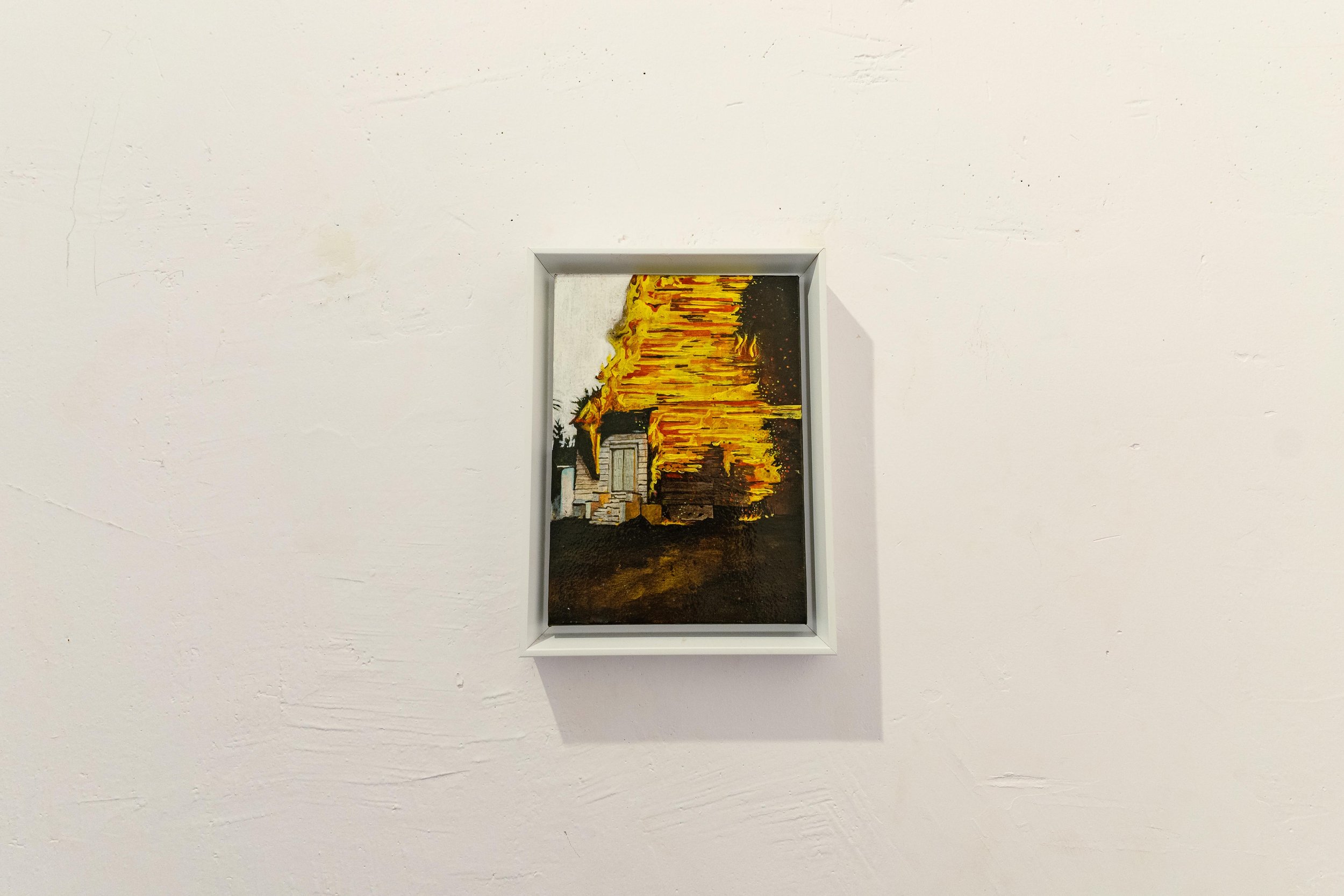

Sahil Naik carefully studies civilizational clues that came from the ocean and extracts image-representations of distant landscapes, non-native flora and fauna, executed by people who had never travelled, but constructed these based on stories and verbal descriptions. Not essentially accurate, but imaginative and localized, Naik is interested in the transplanting of images and natural history, and the situational ‘new’ this contamination produces. This fragment is based on a mural executed by the nuns of Santa Monica and focused on the water hyacinth that is believed to be brought to India by Warren Hastings from the Amazons. The flower also features in Rai’s work where the freshwater hyacinth, the saltwater octopus, and the diver coexist in a floating island entanglement. She “considers how—plants, animals, and people—are enmeshed in a shared world that defies simple boundaries, urging us to reflect on the consequences of both our separate and our entanglements”. Along with the Hyacinth, another flower came from the Americas aboard ships - the Lantana. Its delicate, multicolored blossoms—ranging from soft yellows and pinks to deep blues and greens—are mirrored in the painting. “Locals have an old anecdote likening the plant to a seductive guest who overstays their welcome, reflecting its paradoxical allure and how it damages local flora”. Undaviya has also painted “Inferno of Bloom and Boundary” that captures moments suspended between creation and destruction, where a structure succumbs to a towering blaze - a golden flame. The fire surges upwards - a chaotic symphony of yellows, oranges, reds - flickering with fierce vitality. Each lick of flame mirrors the exuberance of Lantana ca blossoms—vivid, seductive, and untamed.

Sheshdev takes impression prints of algae producing an archive, where he studies their characteristics. “I am becoming more familiar with the ecosystem of water, as well as the labor involved, the storytelling aspects, and the elements of water bodies” he notes.

Shailee Mehta | Shashikant Mohanty | Mahavir Wadhwana | Ushnish Mukhopadhyay | Ritesh Khowal | Aditya Puthur

In Shailee Mehta’s Pickling, we see an intimate, mythical interaction between a scavenging bird (the red kite) and the resting female body. There is a shift from the human gaze to that of a bird as it observes the body laying seemingly at rest, drawing our attention to “how equally and continuously wounded they are by their environments”. The gaze continues to form a portrait in Mahavir Wadhwana’s mind, long after he’s encountered someone on a journey. Her thought lingers, as a natural attraction takes over. In Sashikant Mohanty’s work we see images layered over images. This overlay of man onto landscape, man onto man and architecture on to man produces both a sensation of depth and suggested movement. There is a violence to this image - literal, circumstantial and bodily. Ushnish Mukhopadhyay’s "Sparks in the Void" portrays a solitary survivor in the silence of the post-apocalyptic event. The weight of starting over, whilst healing from the violence of an end produces a state of suspension - one that sits between life and death.

An in between space between life and death is also that of sleep. “Where do we go when we go to sleep?” asks Ritesh Khowal. Our bodies are our stake in the physical world - the drawing presents this body in space-time contemplation prior to falling asleep. This contemplation and/or recollection is key to the body to enter a fluid state that penetrates a third realm.

Puthur’s still-life titled The Dilution Delusion is a critique of the alternative medicinal practice of homeopathy rooted in the myth of vitalism. In the painting, the homeopathic remedy Arsenic Album 30C is displayed on a torn and crumpled page from an 11th-grade chemistry textbook that explains basic chemistry concepts. Arsenic Album 30C was recommended by the Ministry of AYUSH and highly promoted as a prophylactic for COVID-19, particularly for frontline workers and senior citizens, with the belief that it would help strengthen community immunity against the pandemic.

Mahima Verma | Pakhi Sen | Girish Naik | Amshu Chukki | Anikesa Dhing

Mahima Verma draws a barbed line through the landscape reminding us of borders and how the vastness of this planet is consistently challenged by narrow ideas like nations, ownership and other kinds of political, cultural and theological frameworks. Pakhi Sen approaches the home as a part of a larger ecosystem where we interact with welcome and sudden guests. The movement of small creatures in our surroundings are “haunting yet familiar” she writes. Here the window like the fence in Mahima’s work becomes another device to view the world from. It is both a conduit and a separation. Noting the “fragile tension between comfort and disruption… this separation between inside from outside, yet the boundary remains porous, disturbed by the creatures that share the space”. This balance continues to thread through Girish Naik’s untitled gouache on paper, looking at Kulaagars, traditional houses, and farming - recalling a way of life based on the harmony of the many natural elements and practices. Amshu Chukki’s Engadin Diaries is an exercise in encountering, observing, and occasionally absorbing a landscape the artist first arrived in 2014 and has since returned to. The mountains, valleys, and waters – snow-capped and lush, are both a site of tranquility and an aspiration to adventure. The artist uses the simultaneous color printing technique of viscosity to render the strangeness of this seemingly familiar landscape. Anikesa Dhing invokes the thought of dark ecology “wherein both human and non-human nature coexist”. Here the Bisleri bottle has over time become a part of the tree, elevated by its roots and has also served as a home for a pigeon - a chance evolution on non-biodegradable materials.

Lakshya Bhargava | Rumit Donga | Purvi Sharma | Yogesh Hadiya | Manas Naskar

Many traditional healing practices assert that diseases arise from imbalances in vital forces, but these theories contradict well-established scientific knowledge.

The taming of the wild into aesthetic gardens can be read as a form of control, but also a cat of care. They both require tending. Humans have since ancient times developed devices starting from irrigation in the Jordan valley, to farming techniques, leading to medicinal and sacred groves and colonial botanical gardens. Another kind of pleasure is enacted in the bamboo groves of the Cubbon park in Bangalore created in 1870 under Major General Richard Sankey, then British Chief Engineer of Mysore State. A spot for queer men to meet and have fleeting sexual encounters with the act of cruising is seeing a rapid decline with the proliferation of dating apps and gentrification of these otherwise solitary spots. For me, cruising embodies the act of being in a space, searching, and engaging in the playful tension of the gaze—a romanticized interplay of desire and foreplay.

Purvi Sharma while talking about Man Made Forest (year) notes “that forests, like agricultural practices, are both natural and human-made”. This observation emerges from her time in the village of Siwan in Bihar, where the natural landscape of lush wheat and mustard fields; the scent of crops, and the sounds of wildlife contrast with the noise of industrial activities. "Barren Dreams" depicts a lone monkey-farmer's resilience in the face of despair. He plants seeds into the cracked soil of a vast barren field that stretches into the horizon, surrounded by remains of failed crops and abandoned farms. This scene highlights farmers' struggles symbolizing lost hope. Being a villager I am accustomed with the lush vegetation, varied foliage and plenty of open spaces devoid of urban settlements. Trees, bushes, and distant horizon had always been a sustenance to the eye and mind. My surroundings are still thriving with greenery and having been born and brought up in this lush nature, all these are deeply embedded into my subconscious. It is very obvious for me to respond to it.

Madhav Vyas | Nehal Parkar | Rajaram Naik | Pritesh Naik

In Madhav Vyas’s Anusaran, we see acts of repetition in rituals that bring bodies and minds together in united intention and resolve. The bodies, represented by hands merge into a form of collective being thinking about interconnectedness and harmony. Nehal Parkar’s Karit reflects on another ritual that involves the Cucumis melo var. agrestis, or karit. The bitter melon is broken with the tip of the toe, and its juice tasted as a gesture to embrace bitterness before sweetness in this entwinement of nature and culture. The fruit is also poked with sticks to resemble an animal as it stands in offering.

Rajaram Naik invokes the boar avatar of Vishnu that lifted the earth from the depths of the primordial ocean. The boar, now considered a pest in Goa is used as a symbol of resilience and a guardian of the planet. Ultimately Pritesh Naik questions the politics of authenticity that is being used to polarize communities in the vein of native/non-native, religion and caste politics. The cashew plants that came to India with the Portuguese, but became an intrinsic ingredient in local culture - the fruit and its byproducts - distilled through a range of traditional processes. What is authenticity then - the fruit, the process of its harvesting and or extracting of its by-products or its industrial, packaged life?